Jacque Cousteau's Conshelf Program

Three Groundbreaking Undersea Habitats

Conshelf 1

Diogenes was a Jacques Cousteau brainchild and the first of his three famous Conshelf habitat projects. In fact, it’s recognized as the first true underwater habitat (as opposed to a diving bell, though it wasn’t that different) in human history.

Diogenes was supported by Cousteau’s surface support vessel, the Calypso. It supplied fresh air continuously via a compressor, hot water for showers from a water heater, electricity, and both television and radio signals so the aquanauts wouldn’t suffer boredom.

Diogenes, named for the ancient Greek philosopher famous for living in a barrel (hence the name, as the habitat was very much barrel shaped) was sunk in 1962 to a depth of 30 feet. This is the maximum depth one can live at without needing to decompress before surfacing.

Mind you this was before George F. Bond perfected the science of saturation diving, so it was simply not known how to safely descend much deeper than that for long periods. It was very much experimental and pioneering.

The 30 day Diogenes mission was the first recorded observation of a strange psychological effect of living underwater, which was also famously observed during Tektite 2 missions: Aquanauts would become chummy and insular with each other, seemingly undergoing some sort of psychological synchronization, but easily irritable and hostile towards surface support workers.

Something about how human physiology, the brain included, adapts to life under increased air pressure and in confined spaces makes fellow aquanauts easier to get along with than people still adapted to surface pressure and other conditions.

Cousteau famously speculated that this would lead to separatist undersea settlements declaring independence from land, and that by the year 2000, people would be born, live out their lives and die beneath the sea.

That vision hasn’t yet come to pass, but seems closer than ever before thanks to the explosion of offshore fish farming, deep sea mining and other oceanic resource development projects which require a long term, on-site human presence. Perhaps his dream may still come true?

Conshelf 2

Diogenes was austere to say the least: tiny, cramped and rudimentary. By comparison, Conshelf 2 was a quantum leap forward in every way.

Conshelf 2 consisted of not one, but three habitats positioned close to each other at Shaab Rumi, in the Red Sea of Israel. It was established in 1963 and remains one of the most grand and ambitious undersea living projects ever undertaken.

Costing 1.2 million dollars in 1963 money, the only way Cousteau could afford it was to sign a film contract. Thus, “World Without Sun” was filmed, a documentary about the establishment and occupation of the Conshelf 2 “underwater village”.

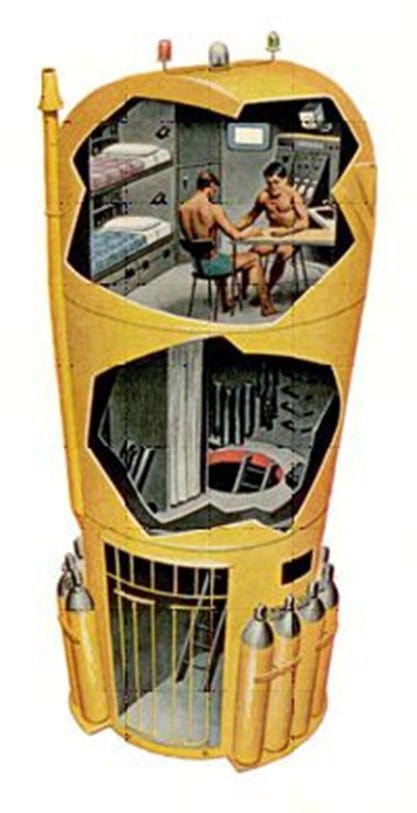

Starfish House, the main lodge, supported six men at a depth of 33 feet for one month. Deep Cabin, positioned at a depth of 90 feet, housed two men for a one week visit. The purpose of Deep Cabin was mostly to test out mixed breathing gases which were a new development at the time.

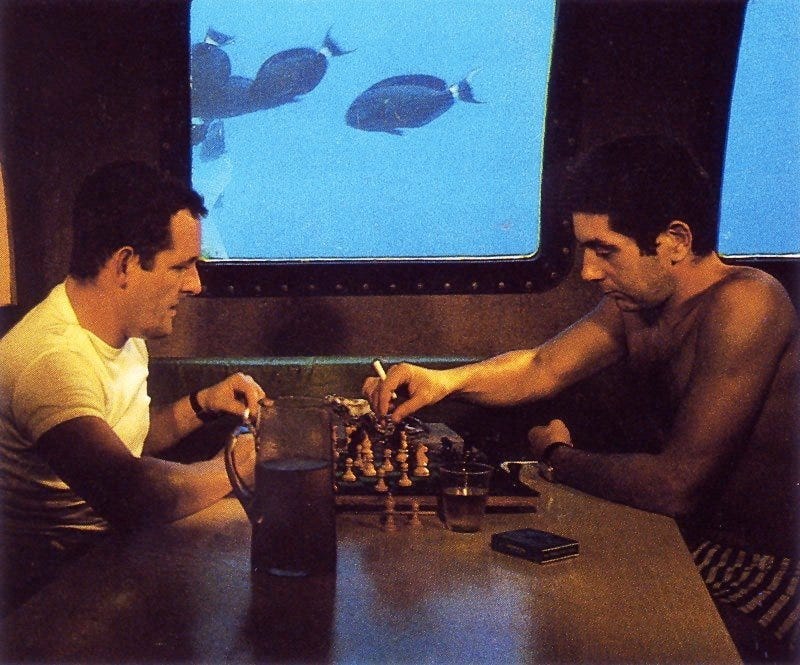

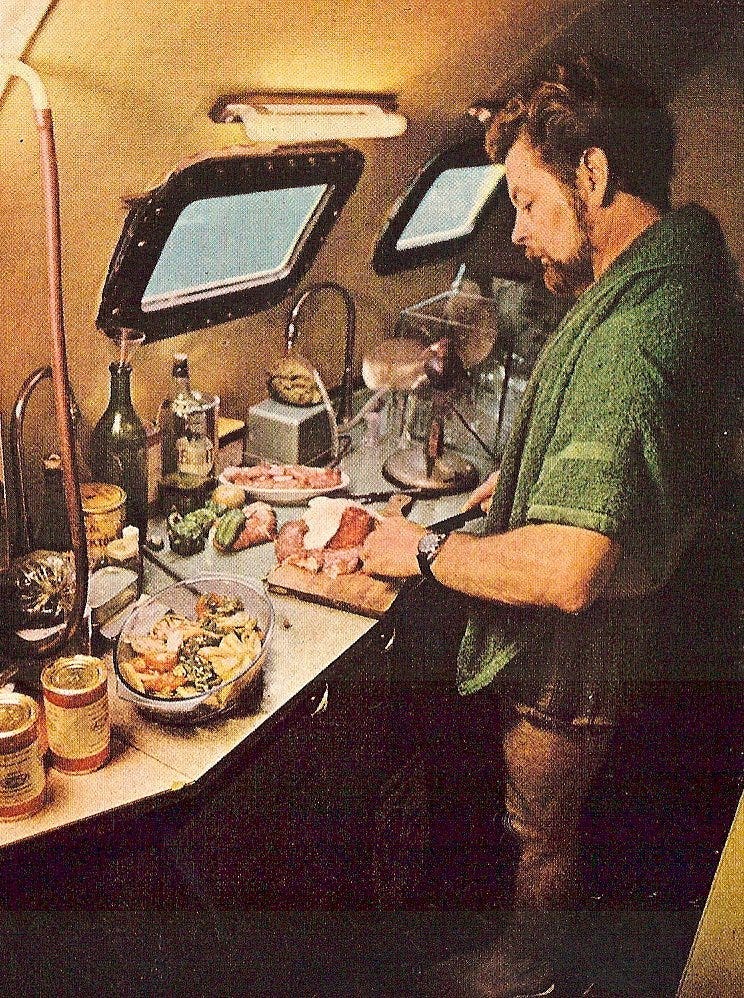

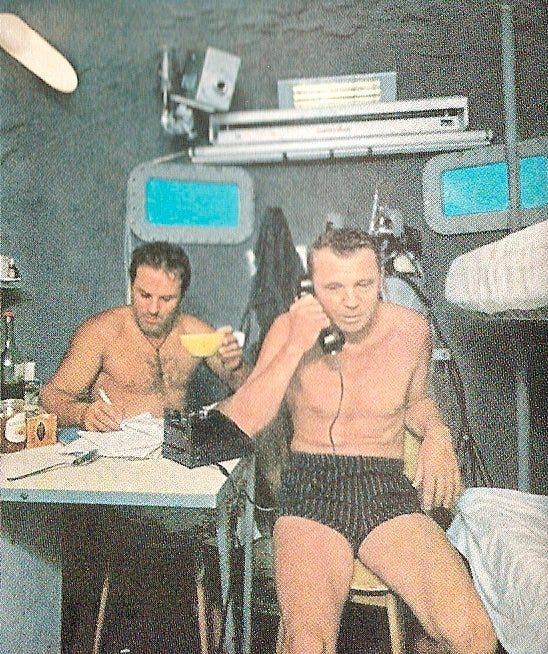

The aquanauts had every amenity of a house on land. Hot showers, television, radio, even a tanning bed for ensuring they got the vitamin D needed to stave off depression. This later led to the use of full spectrum lighting aboard submarines. They even had a resident chef, which assuredly did much to improve morale.

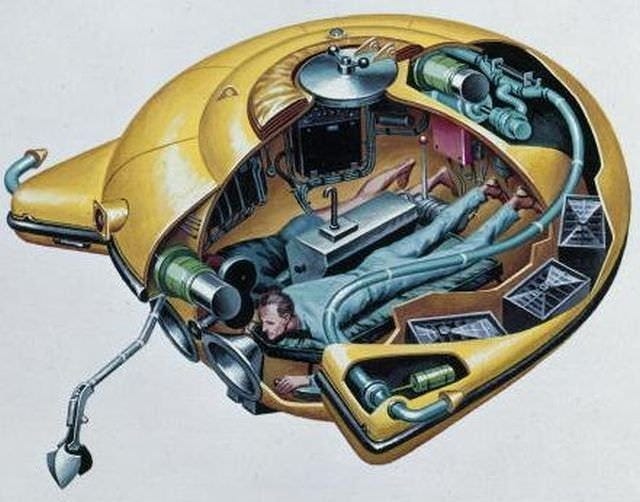

The crew included Albert Falco, who if you’ll recall also participated in Conshelf 1. Jacques’ wife paid a visit to the habitat, as did a parrot that was used as the proverbial “canary in the coal mine” to detect potentially unsafe buildup of CO2. Below you can see cut-away diagrams of Starfish House, Deep Cabin, and the submersible hangar as well as the “Diving Saucer” submersible that it housed:

As you can see, where Hydrolab received a submersible via docking collar, Conshelf 2 instead had a dedicated structure with an open moon pool in the floor which the Diving Saucer could surface through. This provided a dry space into which the submersible could be fully raised, such that its oxygen and batteries could be refilled, and repairs could be effected if necessary.

Conshelf 2 was not a single habitat project then, but really multiple at once. Which as you might expect made it a logistical nightmare. Many things went wrong, mostly to do with helium from the heliox breathing mixture seeping out through the spots where cables passed through the hull. This caused Deep Cabin to flood a little bit, over and over, until the cause was discovered.

A lot of valuable science got done as well though, mostly to do with the effects of protracted underwater living on human biology. It was discovered that higher concentrations of oxygen in the air caused hair and fingernails to grow three times faster, and sleep became especially restful and regenerative. These findings led to the medical use of hyperbaric chambers in hospitals to accelerate healing.

Conshelf 2 had many “firsts”. It proved the value of putting humans in the ocean for long term scientific observation. It demonstrated the utility of providing someplace already underwater from which to deploy and recover a deep diving submersible, avoiding the perils that come with doing so from an A-frame ship (especially in choppy surface conditions).

Perhaps the best way to communicate what a marvel Conshelf 2 was at the time (and today) is to simply direct your attention to Le Monde Sans Soleil, or “World Without Sun”, the documentary Cousteau produced about the Conshelf 2 project.

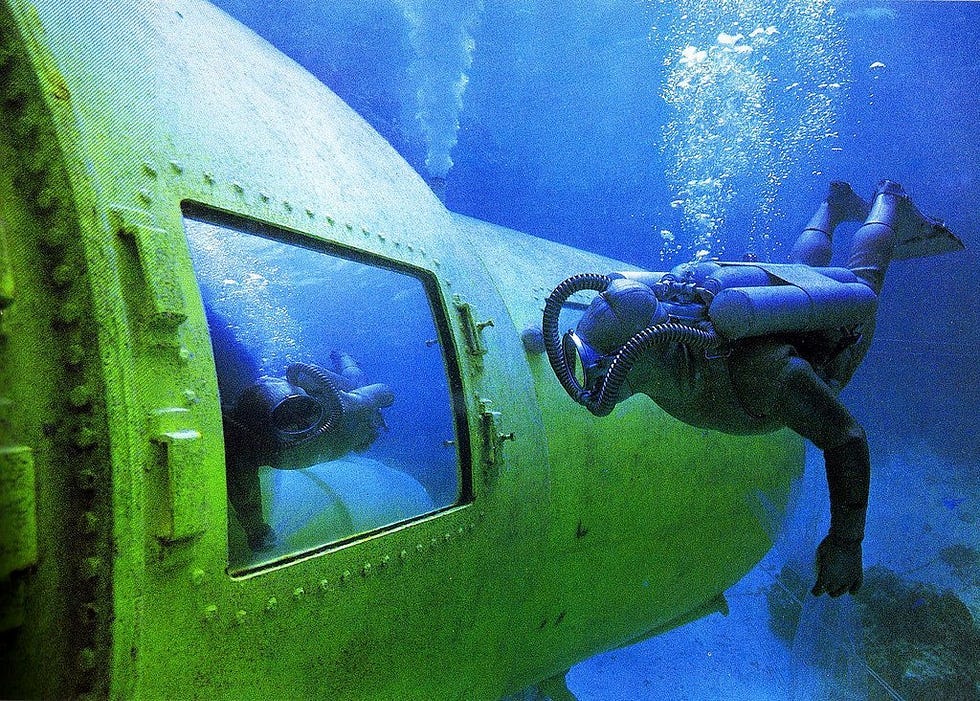

Today, sadly, all that remains of Conshelf 2 is the grown-over husk of the sub hangar. The rest, as is all too common, was hauled up out of the sea and sold for scrap. The hangar is accessible to scuba divers, but the windows have been smashed so as to flood it, lest anybody try to live inside it.

Conshelf 3

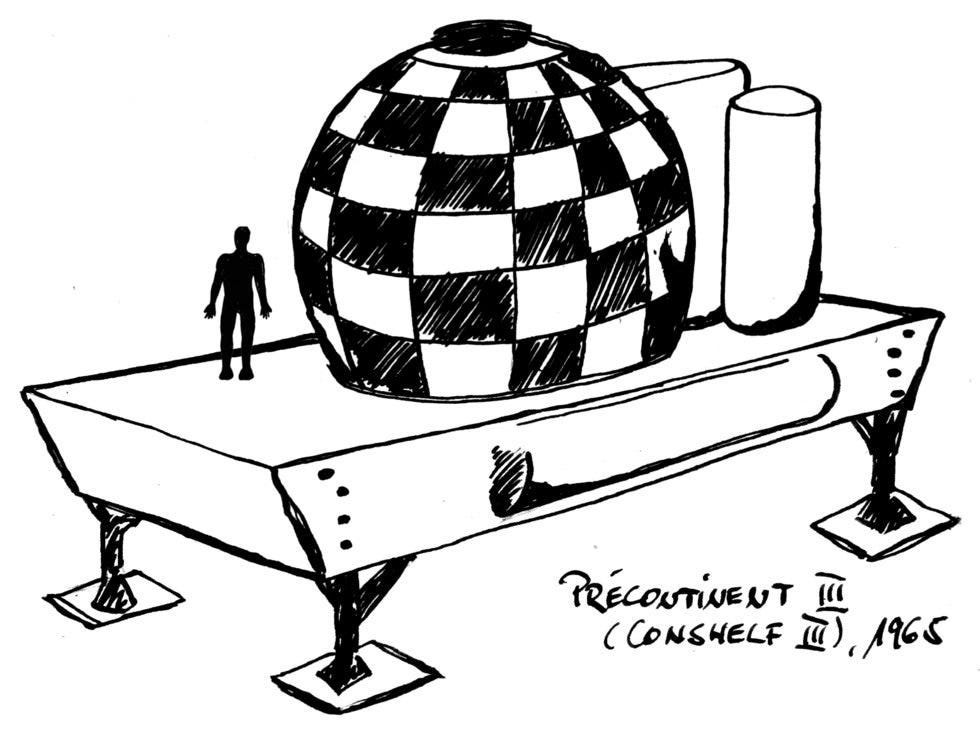

Of course now I’ll move on to the final habitat project ever undertaken by Jacques Cousteau. That’s right bitches, it’s time for Conshelf 3, the biggest and baddest of them all.

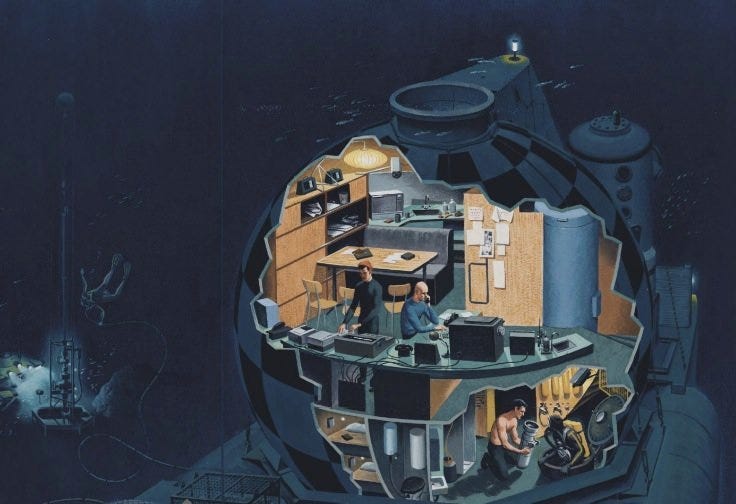

If it looks less beautiful and fantasy-esque than Conshelf 2, it’s because Conshelf 2 was intended to be beautiful and a showpiece for the documentary about it. Conshelf 3, instead, was all business. Specifically it was a prototype for an underwater oil rig.

Funded entirely by the French petrochemical industry, Conshelf 3 was the first serious attempt to demonstrate the feasibility of putting humans underwater, long term, for the purpose of oil extraction. This was before robotics was advanced enough that ROVs could replace divers for most oil related tasks.

This was also before Cousteau had his environmentalist awakening, after which he did a 180 on the topic of human settlement of the sea, instead proclaiming we should stay out of the ocean and focus on conserving its biological diversity.

Imagine the consternation of his wealthy financiers when he did this. In all likelihood this was the turning point where they began looking for other ways than Cousteau’s habitat technology to extract undersea oil deposits.

Of course today, the “habitat” is on the deck of the ship (the deco chamber) and the divers are shuttled between it and the work site by a pressurized diving chamber. More on that later.

Conshelf 3 was deployed on September 17, 1965. It was emplaced on the sea bed at a depth of 100 meters, three times the depth of Conshelf 2. The habitable portion consisted of a sphere 15 meters across divided into two floors, roughly as spacious as Starfish House before it.

Because of the spherical hull, Conshelf 3 could be sealed up and used as a decompression chamber. It also had its own ballast tanks and so could lift itself up off the sea bed and float to the surface for relocation as desired, an important feature for a structure originally intended for oil extraction. When the deposit is depleted, the entire habitat would relocate.

What a shame that didn’t become the standard. Instead, as mentioned before, the way it’s done today is for aquanauts to descend to the work site in a pressurized diving chamber which serves as their base of operations for each 12 hour work period. (Seen above)

When they are finished for the day, they climb back inside, seal it and the chamber maintains the pressure they are adapted to on the way back up to the ship. If 12 hours of labor at the bottom of the sea sounds dangerous and miserable to you, it is. That’s why it pays famously well.

Once at the surface, the diving chamber is carefully docked to the shipside decompression chamber, as a crew capsule docks to the ISS. The deco chamber also has the higher air pressure inside they became acclimated to while working at depth. Here, they can relax and wait out the many hours of decompression necessary before they can safely exit the chamber.

Had things gone differently between Cousteau and his backers, perhaps we’d live in a different world today. One where entire submersible oil rigs sit on the sea bed, populated by crews of aquanaut oil workers living and working at depth for weeks, or even months at a time.

Follow me for more like this, or check out my horror fiction (mostly), 50% free with the rest only $5/mo all access